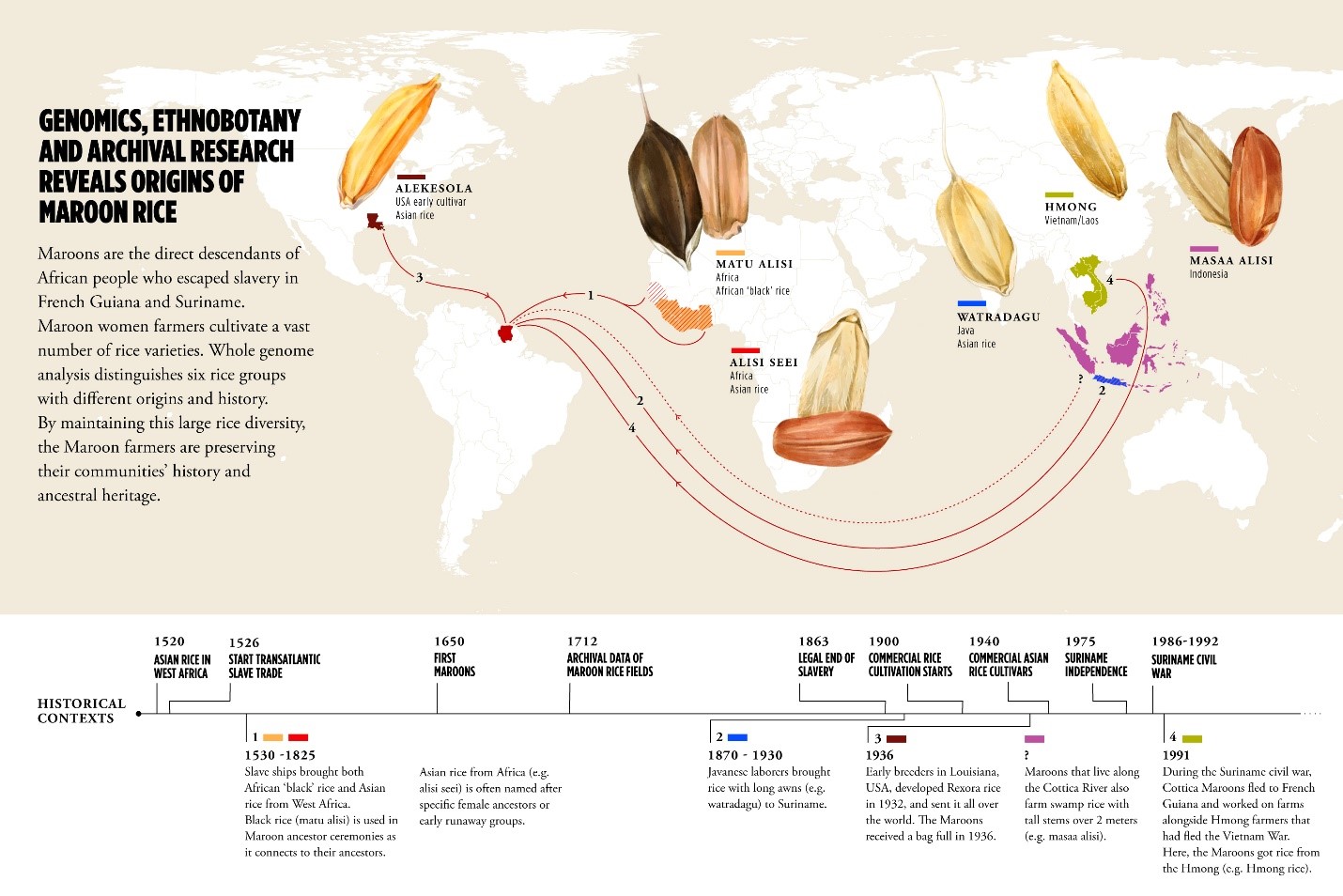

For centuries, descendants of Africans who escaped from slavery, known as Maroons, have been growing rice in the interior of Suriname and French Guiana. New genetic research combined with ethnobotany by Wageningen University & Research and Naturalis Biodiversity Center has unraveled the origins of Maroon rice, linking it to 350 years of colonial history.

The talesof the ancestors

Between 2017 and 2023, Ethnobotany professor Tinde van Andel and PhD candidate Nicholaas Pinas interviewed nearly 100 women in the interior of Suriname and French Guiana. What types of rice do they plant and where do they think it comes from? Many stories supported the idea that their ancestors brought the rice with them from West Africa. When collecting the stories, it was helpful that Pinas himself comes from a Maroon community: "I have family there and I speak the languages. Once you’ve talked to one woman, she will direct you to another woman in another community. As a researcher, it’s essential that you build a relationship of trust."

Rice is a staple food of the Maroons. For centuries, people in Suriname and French Guiana have been eating rice from their own fields located in the forest around the settlements. Traditionally, women have been responsible for growing the rice, which explains why many varieties have women's names. The rice often bears the name of women who had rebelled against plantation owners or who had heroically managed to escape slavery and smuggled rice seeds on their flight, such as alisi Seei, 'the rice of Seei', a woman originally from Ghana.

Rice forceremony

In Professor Eric Schranz's Biosystematics group, evolutionary biologist Marieke van de Loosdrecht sequenced and compared the DNA of 136 Maroon rice varieties to a diverse worldwide panel of rice landraces and varieties. The analysis found that many of the Maroon varieties are genetically related to early cultivated varieties from West Africa. "During the transatlantic slave trade, both African black rice and Asian rice were shipped from West Africa to North and South America,” she explains. “Fleeing Maroons took the seeds from plantations to the interior." The 'black' rice is indigenous African rice. This is still grown in most Maroon villages, mainly for ancestor ceremonies. The Maroons' oldest Asian rice varieties are descended from rice brought to West Africa by the Portuguese from the Philippines and Malaysia from 1520 onwards.

The history of the countryhidden in the DNA of its rice

According to Van de Loosdrecht, these are not the only rice source regions that can be connected to Suriname's colonial history: "We have also found unique varieties with a long husk and genetic traces typical of Javanese rice. We can link this to the arrival of Javanese contract workers brought to Suriname between 1863 and 1930."

Around 1932, agriculturalists in the United States developed the rice variety Rexora. Some varieties of Maroon rice are descendants of this Rexora rice. Archive sources report that a bag was sent to the Maroons in 1936. Furthermore, the Maroons also grow a variety of Hmong rice. The Hmong are an indigenous group in China, Laos, Vietnam and Thailand. During the Vietnam War, many Hmong fled their country. Some of them settled in French Guiana, having brought their own rice with them and exchanged it with the Maroons.

Climate-resilientrice cultivation

The global rice market is now dominated by a limited number of commercial varieties that can produce large quantities under very specific conditions. Reliance on limited varieties is risky in a rapidly changing climate. According to Pinas, the Maroons have been using a fundamentally different strategy for centuries: "In various places, they are trying many different varieties. Varieties that do well on a wet riverbank, for example, are left there. The genetic variation of all that rice at their disposal is so great that they can easily adapt to changing ecological conditions. They are constantly optimising their agriculture. At the same time, they don't need pesticides and fertilisers."

For centuries, the Maroons have been skilled at growing robust agricultural crops within existing ecological boundaries. This is an important lesson at a time when ecosystems are being degraded and lost.